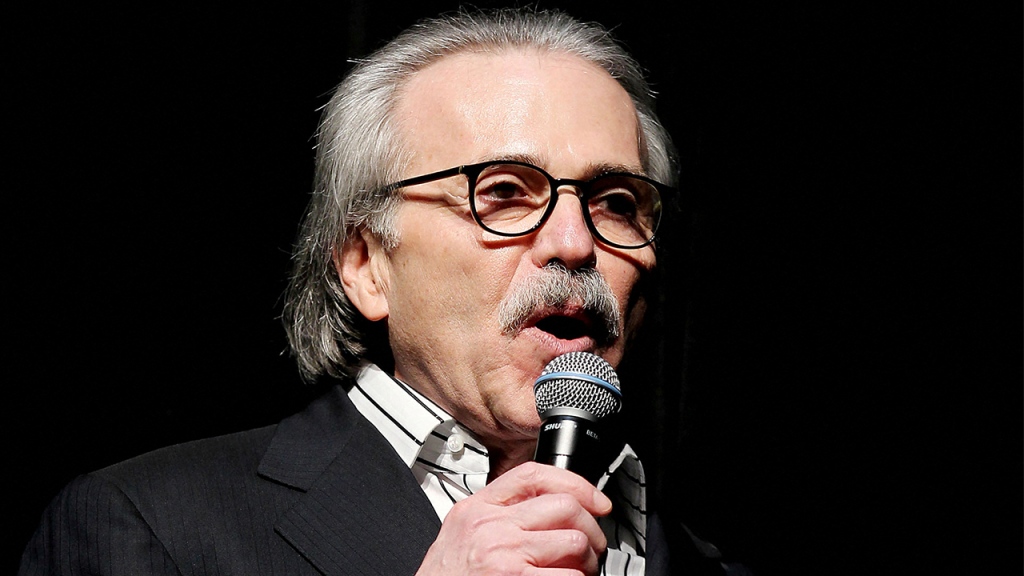

David Pecker, the former head of the National Enquirer, testified under oath about his involvement in catch-and-kill payments to help Donald Trump’s campaign. He admitted to making payments for false stories and to silence Karen McDougal, who claimed to have had an affair with Trump. Pecker also mentioned that his duty to the campaign was to prevent damaging stories about Trump from being published elsewhere. He discussed being asked by Trump and Michael Cohen to help the campaign by running or publishing positive stories about Trump and negative stories about his opponents.

Pecker described how Cohen would contact him to kill negative stories and even create fake news to slander Trump’s political opponents. He mentioned notable fake stories such as “Ted Cruz Sex Scandal: 5 Secret Mistresses” and “Bungling Surgeon Ben Carson Left Sponge in Patient’s Brain.” He recalled being asked how he and his magazines could help the campaign and responded by running or publishing positive stories about Trump while defaming his opponents. Pecker also highlighted the ease with which Cohen would provide information to embellish fake stories.

Despite paying McDougal to remain silent during the campaign, Pecker mentioned that Trump was hesitant, warning that such stories would eventually resurface. However, Pecker insisted on the payment to suppress McDougal’s story. He explained that the Enquirer arranged for a $150,000 payment for McDougal to write a fitness column in another magazine within the same parent company. None of these details directly relate to the falsified business records, which is central to the legal case. The prosecutors are aiming to establish Pecker’s credibility through his testimony under a previous grant of immunity.

Pecker will continue his testimony regarding the Stormy Daniels story, which is at the heart of the case, with the trial taking a break for the day. The judge heard arguments about Trump’s alleged violations of the gag order by attacking other witnesses such as Cohen and Daniels. Prosecutors accused Trump of violating the gag order multiple times and suggested a fine for each occurrence. While Trump’s lawyer argued that there was no willful violation, the judge expressed frustration at the lack of specific responses to his questions.

The judge did not make a decision on the alleged violation of the gag order by Trump but indicated a clear intention to address the issue. Despite arguments from Trump’s lawyer about his client being allowed to respond to attacks, the judge emphasized a lack of credibility from the defense. The hearing highlighted the tension between the legal teams and the judge’s effort to ensure compliance with the gag order. The unfolding trial involving Pecker’s testimony sheds light on the intricate relationships between media figures, politicians, and legal proceedings.