New York plans to celebrate Transgender Day of Visibility by lighting up 13 landmarks in light pink, white, and light blue colors. The state will join the White House in observing the day, showing support for transgender individuals. Governor Kathy Hochul expressed pride in the strength of transgender New Yorkers and reassured them that they are always welcome and loved in New York. Events are scheduled around the world to honor the day, including panels, marches, and inclusive activities like roller derby games and picnics.

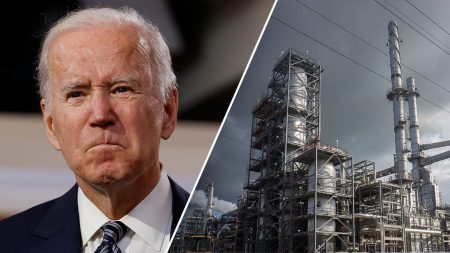

President Biden received backlash on social media after announcing Transgender Day of Visibility on Easter Sunday. Despite the controversy, the day is meant to honor the courage and contributions of transgender Americans and promote equality for all individuals. The White House released a statement reaffirming the nation’s commitment to creating a more perfect union where everyone is treated equally throughout their lives. Secretary of State Antony Blinken also emphasized the importance of allowing transgender individuals to live authentically, safely, and with dignity.

International Transgender Day of Visibility was first organized in 2009 by Rachel Crandall-Crocker, the executive director of Transgender Michigan. The day was created to bring together the transgender community worldwide and combat discrimination by fostering understanding and unity. Crandall-Crocker expressed the importance of a day when transgender individuals do not have to feel lonely and can come together as a community. The day has grown over the years to become a global observance with events and activities happening around the world.

In addition to New York’s landmarks being lit up in celebration, other events are planned in different locations including a rally on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The day will also be marked by marches, panels, and various activities in cities like Cincinnati, Atlanta, Melbourne, and Philadelphia. These events aim to raise awareness about the transgender movement and honor the diverse contributions of transgender individuals. Despite criticism from some quarters for the timing of the day coinciding with Easter Sunday, the day remains an important opportunity to recognize and support the transgender community.

Amidst the celebrations and events scheduled for Transgender Day of Visibility, there has also been controversy surrounding the timing of the day falling on Easter Sunday, a significant Christian holiday. Some critics have accused President Biden of insensitivity for marking Transgender Day of Visibility on Easter Sunday, while others have expressed support for recognizing the contributions and rights of transgender individuals. Despite the differing opinions, the day serves as a reminder of the ongoing struggle for equality and acceptance faced by the transgender community.

Overall, the observance of Transgender Day of Visibility is an opportunity to celebrate the courage, contributions, and resilience of transgender individuals around the world. The day highlights the importance of creating a more inclusive and accepting society where everyone can live authentically and with dignity. Through events, activities, and gestures of support like lighting up landmarks, the day aims to raise awareness, foster understanding, and promote equality for all individuals regardless of their gender identity.